Nathanael West’s Claude in The Day of the Locust (1939) reflects with a whimsical pessimism, that:

Love is like a vending machine … You insert a coin and press home the lever. There’s some mechanical activity inside the bowels of the device. You receive a small sweet, frown at yourself in the dirty mirror, adjust your hat, take a firm grip on your umbrella and walk away, trying to look as though nothing had happened.

Chill hangout boasting a full can bar, old-school arcade games and pinball machines in a low-key setting. The Coin Slot Cart 0. The Coin Slot Drinks Merch Gallery Find Us Cart 0. The Coin Slot Drinks Merch Gallery Find Us.

The machine says, Place another coin in the slot, My, The machine says, That you do sure ask a lot, And, Then what, You're tying the machine streams into a defusing knot, And, Then what, Coin in the slot, coin in the slot, Oh, Here's another coin, And, Then what, The birth of humanity with crying babies in a gigantic cot, And, Then what, If you. The Las Vegas Sun has an article on the transformation of the slot machine from coins to TITO if you’re feeling nostalgic. If you’re in Vegas you can head to the Golden Gate where they have about 5 slot machines like the one above from when they first opened. I’m not very nostalgic and even I think they’re cool.

The analogy is funny partly because it seems to propose a correlation between the act of sex and that of operating the machine; the rumbling ‘bowels’, the delivery of the ‘small sweet’, the scowl into the mirror, the dirtiness of the mirror, the adjustment of the hat, the ‘firm grip on your umbrella’, and the deliberately indifferent departure, all implicitly represent the stages of a sexual encounter. And yet, there is nothing obviously sexual about any of this. West’s analogy misbehaves as an analogy by losing sight of its subject – it’s fickle in this sense – but in doing so it introduces a new element into the novel’s account of early twentieth century America: the phenomenon of the slot machine transaction. West doesn’t do anything more with this idea, having broached it under the flimsy pretence of talking about love, but, in a way, there isn’t much that he could have done with it. Slot machine transactions were what they were: you inserted your coin, received your sweet or whatever trifle it was you were being sold, adjusted your hat, and walked away.

Slot machines were everywhere in the first half of the twentieth century, yet they appear very rarely in its literature. Thomas Edison’s coin-operated ‘talking machine’ of 1877 – the first ‘automatic amusement machine’ on record – was much more popular than his phonograph in the early years, yet Villiers de l’Isle-Adam’s novel L’Ève Future (1886) focuses exclusively on the latter in imagining a futuristic ideal woman. Coin-operated cinemas outnumbered film theatres massively in the modernist period – appearing in drugstores, theatre lobbies, lecture halls, train and ferry stations, and entertainment parlours – and were also much cheaper than cinema tickets, costing just a penny or nickel. However, it is cinema that turns up everywhere in modernist literature: as David Trotter writes, the modernists were ‘fascinated’ by it. The growing bulk of criticism on modernism’s imaginative debt to film bears witness to this fascination, while modernist criticism and cultural theory alike – like the modernists – have almost nothing to say about slot machines. Erkki Huhtamo’s ‘Slots of Fun, Slots of Trouble: An Archaeology of Arcade Gaming’ (2005) begins by remarking on the peculiar absence of the slot machine from treatments of America’s entertainment culture, and his ‘archaeology’ runs out of steam after an essay’s worth of discussion.

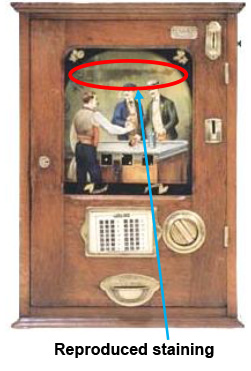

The problem with writing about slot machines from a cultural or ‘archaeological’ angle, as opposed to a historiographic one, has to do with the disproportion between the quantity of information that exists about them and the slimness of the grounds for analysis. I could tell you that slot machines sometimes sold ant eggs, or tin eggs filled with sweets, to the accompaniment of cackling chickens, and that – although a slot machine transaction wasn’t analogous to love, or sex – it could simulate a bedside manner; some machines diagnosed illnesses, and prescribed and proffered medicines. Yet none of this was sufficiently interesting to the writers with whom they coincided to inspire much thought.

John Rodker’s Adolphe, 1920 (1929) is among the few modernist texts to use a slot machine metaphorically, but the coin-operated cinema he uses to configure love is no different from other kinds of cinematic experience in its suggestion of an immersive fantasy, staged in the dark, and automatically. As Laura Marcus writes, ‘[t]he space through which Rodker’s protagonist wanders … is continuous with the optical shows and screens.’ Nothing about Rodkerian romance is tied specifically to the penny-operated mechanism. Similarly, the slot machine strip show to which Bloom links his engagement with Gerty in Ulysses (1922) simplifies it to the point of distortion; the kinetoscope caption ‘A dream of wellfilled hose’ of which Gerty reminds him, works, like lots of Joyce’s associations, by shifting the focus forward in a new direction – though the new direction embodied by the slot machine is momentary, spanning just six lines.

Slot machines seem like an appropriate reference point only when the idea they describe is superficial. So, obsession in Rodker, voyeurism in Joyce, and sex in West are too complex to be invoked by a cheap, thirty second, mechanical transaction – particularly in the 1920s and 1930s, when automated shopping had become commonplace. Photobooth and automat companies set out to offer the kinds of uniform satisfaction that had secured the success of the Ford Motor Company and the chain store. The New Yorker who discovered an obscure aggressor in her automat sandwich in 1925 – ‘no one could determine if it was a small reptile or just a pugnacious insect’ – was an exciting exception to the rule of total predictability. Similarly, the automat inveterate whose wife poisons his sandwich in Colonel Woolrich’s ‘Death at the Automat’ (1937) – as if to punish and vindicate his avoidance of her cooking in the same act – is an unlucky anomaly. Slot machines normally suggested normality. In George Orwell’s Coming Up for Air (1939), ‘one of the penny-in-the-slot machines … you know those machines that tell your fortune as well as your weight’ is typically nonsensical in its attempt to estimate George Bowling’s future (‘you will rise high!’) and in its revelation of his weight gain (‘Must have been the booze.’) For Sartre, too, in La Nausée (1938), the fortune dispensing slot machine is an image of hackneyed conversation:

[P]ut a coin in the slot on the left and out come anecdotes wrapped in silver paper; put a coin in the slot on the right and you get precious pieces of advice that stick to your teeth like soft caramels.

Slot machines and ‘pseudo philosophy’ both suggest the cloying persistence of conventions which Sartre’s Roquentin is keen to replace with his own style of ‘nausea’ – which at least has the virtue of making him think.

Slot machines landmark a form of shallowness that Sartre’s Roquentin and Orwell’s Bowling struggle to overcome in the course of reinventing themselves. For both characters, too, they suggest the resistance that seems to be posed by modernity – in the sense of the aggregate of modern things – to self-reflection, and reflection in general.

In Louis MacNeice’s ‘In Lieu’ (1962), this resistance develops into an impasse; the poem characterises modernisation as the process whereby objects lose their ‘savour’ (‘The savour is lost’) – meaning both ‘flavour’ and ‘savoir’ – because MacNeice understands the sensory textures of experience as the key to its knowability. He writes:

Roses with the scent bred out,

In lieu of which is a long name on a label.

Dragonflies reverting to grubs,

Tundra and desert overcrowded,

And in lieu of a high altar

Wafers and wine procured by a coin in a slot.

‘-lot’ reconstitutes ‘alt-’ in a way that deprives it of altitude; the adjustment is lowering. MacNeice’s ‘coin in a slot’ is completely devoid of the magic associated with the slot machines of the turn of the century, and with which non-urbanites continued to associate automat cafés until as late as the 1940s. In John Cheever’s ‘O City of Broken Dreams’ (1948), the country-based Molloys are delighted with the way the glass doors of the food compartments ‘spring open’ at New York’s most famous automated restaurant. But MacNeice’s automat is dishearteningly literal – its wafers and wine lack the ceremony of sacramental significance. Something has been lost in the act of adaptation – or ‘bred out.’ This flattening effect may be linked to the malaise of Edward Hopper’s solitary coffee drinker in Automat (1927), whose crossed legs and hat repeat the shapes of the reflected lights and fruit bowl upside down, as if she were equally lifeless – though Hopper’s minimalism is romantic: he doesn’t include the slot machines that would have lined the walls, just as he leaves out the ‘Photomaton’ from the scene he reproduces in Chop Suey (1929). Slot machines seem not to have fitted with the particular form of modern gloom he wanted to recreate – perhaps because they threatened to trivialise it. Hopper finds a dignity in modern life in spite of its monotony, while MacNeice’s modernity is shallow to the point of meaninglessness. His slot machine gains its meaning by describing what it feels like to run out of meaningful thoughts.

Coin Slot Machines Atlantic City

—Beci Dobbin